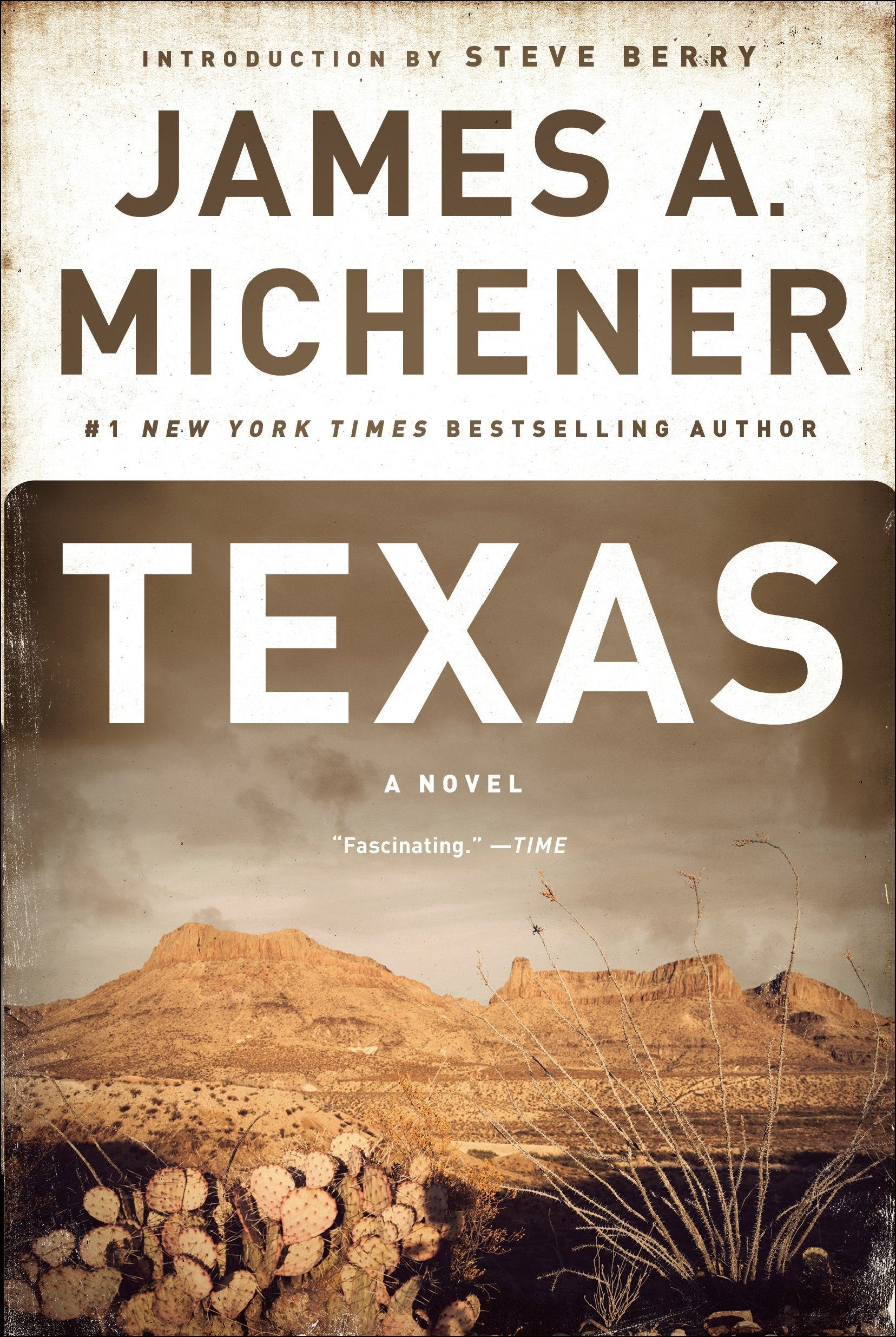

Texas: A Novel

Editorial Reviews

Review

“Fascinating.”—Time

“A book about oil and water, rangers and outlaws, frontier and settlement, money and power . . . [James A. Michener] manages to make history vivid.”—The Boston Globe

“A sweeping panorama . . . [Michener] grapples earnestly with the Texas character in a way that Texas’s own writers often don’t.”—The Washington Post Book World

“Vast, sprawling, and eclectic in population and geography, the state has just the sort of larger-than-life history that lends itself to Mr. Michener’s taste for multigenerational epics.”—The New York Times

“A book about oil and water, rangers and outlaws, frontier and settlement, money and power . . . [James A. Michener] manages to make history vivid.”—The Boston Globe

“A sweeping panorama . . . [Michener] grapples earnestly with the Texas character in a way that Texas’s own writers often don’t.”—The Washington Post Book World

“Vast, sprawling, and eclectic in population and geography, the state has just the sort of larger-than-life history that lends itself to Mr. Michener’s taste for multigenerational epics.”—The New York Times

About the Author

James A. Michener was one of the world’s most popular writers, the author of more than forty books of fiction and nonfiction, including the Pulitzer Prize–winning Tales of the South Pacific, the bestselling novels The Source, Hawaii, Alaska, Chesapeake, Centennial, Texas, Caribbean, and Caravans, and the memoir The World Is My Home. Michener served on the advisory council to NASA and the International Broadcast Board, which oversees the Voice of America. Among dozens of awards and honors, he received America’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in 1977, and an award from the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities in 1983 for his commitment to art in America. Michener died in 1997 at the age of ninety.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

ON A STEAMY NOVEMBER DAY IN 1535 AT THE MEXICAN SEAPORT of Vera Cruz, a sturdy boy led his mules to and from the shore where barges landed supplies from anchored cargo ships. He was Garcilaço, ten years old “but soon to be eleven,” as he told anyone who cared to listen.

The illegitimate child of an Indian mother and a rebellious Spanish soldier who was executed before the woman gave birth, he was soon abandoned, placed in a home that was run by the local clergy, and then turned over to a rascally muleteer as soon as he was old enough to work. That occurred at age eight, and he had been working ever since.

On this hot morning he had to labor especially hard, for his master had received instructions that the mules must leave immediately for the capital, Mexico City—La Ciudad de México—more than a hundred leagues distant (one league being 2.86 miles), and whenever heavy work was required in a hurry the ill-tempered man rained blows upon the boy.

From his father, Garcilaço had inherited a build somewhat heftier than that of the average Indian; from his mother, the smooth brown skin and the black hair that cut across his forehead in a straight line reaching down almost over his eyes. And from some mysterious source he had acquired a placid disposition and an incurable optimism.

Now, as he loaded his mules with the last of their cargo and headed them toward that long and tedious trip through the lowland jungles, he consoled himself with the thought that soon he would see the majestic volcanoes of the high plateau and shortly thereafter the exciting streets of the capital. As he left the port city he hummed a song he had learned from other muleteers:

“Klip-klop! Klip-klop!

There in the sky

The great volcanoes of the plain.

Go, mules! Speed, mules!

For here come I

To climb their lovely path again.”

He had memorized a dozen such songs, one for the mules when they were sick, one for dawn over the pyramids, one for a husband and wife tilling their fields of corn. Since he could not read and had no prospect of ever learning, for he was enslaved to his mules, he used his whispered songs as his bible and his dictionary:

“Klip-klop! Klip-klop!

The smoke I see

Marks where the town hides in the vale.

Go, mules! Speed, mules!

Be kind to me,

And you shall find oats in your pail.”

Each trip up from Vera Cruz was a mixture of drudgery and joy, for although traversing the jungle along poorly kept trails was quite difficult, to travel beside the volcanoes and to see the capital looming in the distance was rewarding, especially since he knew that when he reached it he could count upon a few days of rest and better food. So he kept singing.

On this trip, as he approached the capital, he found his mules competing for road space with unaccustomed hordes of travelers, all going in his direction, and when he asked: “What happens?” he was told: “An auto-da-fé tomorrow. A great auto.”

This was exciting news, for it meant that the streets would be crowded, and that vendors of sweetmeats and tips of roasted beef would be hawking their wares. He himself would have no money to buy such luxuries, but he could rely upon convivial participants to provide him with morsels here and there. An auto in Mexico City, in the cool month of November, could be a memorable affair.

A formal auto-da-fé, act-of-faith, as conducted in Spain could be a lavish public display of the spiritual glory and temporal power of the Catholic church in its determination to root out any deviation from the True Faith. It consisted of marching soldiers, military bands, a parade of clerics in four or five differently colored robes, the appearance of the bishop himself riding in a palanquin borne by four Negro slaves, and the final appearance of an executioner leading in chains the apostates who were to be burned that day. But in Mexico in these early years an auto was a much simpler affair; on this occasion, as Garcilaço learned on entering the city, two men were to be executed, but as his informant explained, their cases were quite different.

“The first man, from Puebla, has behaved properly. He’s recanted his heretical behavior, pleads to die within the arms of the church and will be mercifully strangled by the executioner just before the flames are lighted.”

“Wise man,” Garcilaço said, for he remembered an occasion when an accused had refused to admit his guilt, and his death had been horrible.

“The other man, from this city, is mad with lust for his own interpretation of God’s will. Refuses to recant. Says he’ll welcome the flames. He’ll get them!”

On the morning of the auto, crowds began to gather along the route the procession would take, and as Garcilaço had foreseen, the streets were crowded with vendors, but the greatest crush came at the public square before the cathedral, where stakes had been erected and dry brush piled beneath the little wooden platforms on which the condemned would stand.

Garcilaço found himself an advantageous spot atop a cask, from which he refused to be nudged by latecomers. Doggedly he held his ground, pushing off whoever threatened and once offering to climb down and fight a young man much bigger than he. When this fellow looked up and saw his opponent’s grim determination, hair in the eyes, scowl on the brown face, he desisted, left the cask, and elbowed his way to one less vehemently protected.

At noon, with the sun blazing overhead, Indian women sold in wooden cups cool potions of a refreshing drink they made from the sweet limes for which the valleys near the city were famous, and Garcilaço thirsted for his share, but since he had no coins, the women passed him by. However, a Spanish official who had purchased two cupfuls could not finish his second, and sensing the boy’s desire, handed him a generous leftover. As Garcilaço gulped the drink while the vendor impatiently tapped her foot, waiting for the return of her cup, the Spaniard asked: “You’re a mestizo?” and Garcilaço, between hurried gulps, said: “Yes, my father was Spanish.”

“How did he happen to marry …?”

“I never knew him. They tell me he was executed … before I was born.”

“Why?”

“Drink!” the vendor admonished him, and Garcilaço drained the cup.

“That was good. Thank you, sir.” The man was about to ask further questions when the boy’s master ran along the edge of the crowd in the open space where spectators were not allowed.

“There you are!” he shouted when he spotted his helper, and he was about to pull Garcilaço from his cask when the Spanish gentleman gave the older muleteer a hard shove: “Leave the boy alone.”

“The master hesitated a moment, but when he saw the quality of the man who had pushed him and realized that this stranger was probably from Spain and would have a sword ready for instant use if his honor was in any way infringed, he backed away, but from a safe distance he growled at his assistant: “Bad news! We must deliver our goods to the army in Guadalajara.” Since that city was more than a hundred and forty leagues to the west, Garcilaço knew that the journey would be a continuation of recent hardships, and that was bad enough, but now his master added: “You must come with me now.”

This Garcilaço did not want to do, for it would mean missing the auto, but his master was insistent, whereupon the Spaniard said in a low, threatening voice: “You, sir! Begone or I’ll have at you,” and off the master went, indicating by his furious stare that he would punish his refractory helper when the auto ended.

“How lucky you are!” the Spaniard said when the man had gone. “Guadalajara! Best city in Mexico.” And when Garcilaço asked why, the man said: “From there you can move on to the real west, and along the road catch glimpses of the Pacific Ocean. China! The Isles of Spice!”

He had served as a government official on the western frontier and said: “I’d always enjoy going back. You’re a lucky fellow.”

Now the real business of the auto began, with functionaries running here and there to ensure proper observances, and in the hush before the procession appeared, the Spaniard tapped Garcilaço on the shoulder and said: “Your master, he seems a poor sort.”

“He is.”

“Why don’t you run away? I did. From a miserable village in Spain where I was nothing. In Mexico, I’m a man of some importance.”

“I’d have nowhere to run,” Garcilaço said, whereupon the man grasped him by the shoulder: “You have the world to run to, my boy. You could be the new conquistador, the mestizo who will rule this country one day.”

“He corrected himself: “Who will help Spain rule it.”

“Look!” Garcilaço cried, and into the square where the kindling waited to be lit came four black slaves carrying the poles of a palanquin on which sat a prelate, dressed in deep purple and wearing an ornate miter, who stared steadfastly ahead. He was Bishop Zumárraga, most powerful churchman in Mexico and personally responsible for the arrest and sentencing of the two heretics who were to be burned. It was obvious from his stern countenance that he was not going to pardon the wretches.

The illegitimate child of an Indian mother and a rebellious Spanish soldier who was executed before the woman gave birth, he was soon abandoned, placed in a home that was run by the local clergy, and then turned over to a rascally muleteer as soon as he was old enough to work. That occurred at age eight, and he had been working ever since.

On this hot morning he had to labor especially hard, for his master had received instructions that the mules must leave immediately for the capital, Mexico City—La Ciudad de México—more than a hundred leagues distant (one league being 2.86 miles), and whenever heavy work was required in a hurry the ill-tempered man rained blows upon the boy.

From his father, Garcilaço had inherited a build somewhat heftier than that of the average Indian; from his mother, the smooth brown skin and the black hair that cut across his forehead in a straight line reaching down almost over his eyes. And from some mysterious source he had acquired a placid disposition and an incurable optimism.

Now, as he loaded his mules with the last of their cargo and headed them toward that long and tedious trip through the lowland jungles, he consoled himself with the thought that soon he would see the majestic volcanoes of the high plateau and shortly thereafter the exciting streets of the capital. As he left the port city he hummed a song he had learned from other muleteers:

“Klip-klop! Klip-klop!

There in the sky

The great volcanoes of the plain.

Go, mules! Speed, mules!

For here come I

To climb their lovely path again.”

He had memorized a dozen such songs, one for the mules when they were sick, one for dawn over the pyramids, one for a husband and wife tilling their fields of corn. Since he could not read and had no prospect of ever learning, for he was enslaved to his mules, he used his whispered songs as his bible and his dictionary:

“Klip-klop! Klip-klop!

The smoke I see

Marks where the town hides in the vale.

Go, mules! Speed, mules!

Be kind to me,

And you shall find oats in your pail.”

Each trip up from Vera Cruz was a mixture of drudgery and joy, for although traversing the jungle along poorly kept trails was quite difficult, to travel beside the volcanoes and to see the capital looming in the distance was rewarding, especially since he knew that when he reached it he could count upon a few days of rest and better food. So he kept singing.

On this trip, as he approached the capital, he found his mules competing for road space with unaccustomed hordes of travelers, all going in his direction, and when he asked: “What happens?” he was told: “An auto-da-fé tomorrow. A great auto.”

This was exciting news, for it meant that the streets would be crowded, and that vendors of sweetmeats and tips of roasted beef would be hawking their wares. He himself would have no money to buy such luxuries, but he could rely upon convivial participants to provide him with morsels here and there. An auto in Mexico City, in the cool month of November, could be a memorable affair.

A formal auto-da-fé, act-of-faith, as conducted in Spain could be a lavish public display of the spiritual glory and temporal power of the Catholic church in its determination to root out any deviation from the True Faith. It consisted of marching soldiers, military bands, a parade of clerics in four or five differently colored robes, the appearance of the bishop himself riding in a palanquin borne by four Negro slaves, and the final appearance of an executioner leading in chains the apostates who were to be burned that day. But in Mexico in these early years an auto was a much simpler affair; on this occasion, as Garcilaço learned on entering the city, two men were to be executed, but as his informant explained, their cases were quite different.

“The first man, from Puebla, has behaved properly. He’s recanted his heretical behavior, pleads to die within the arms of the church and will be mercifully strangled by the executioner just before the flames are lighted.”

“Wise man,” Garcilaço said, for he remembered an occasion when an accused had refused to admit his guilt, and his death had been horrible.

“The other man, from this city, is mad with lust for his own interpretation of God’s will. Refuses to recant. Says he’ll welcome the flames. He’ll get them!”

On the morning of the auto, crowds began to gather along the route the procession would take, and as Garcilaço had foreseen, the streets were crowded with vendors, but the greatest crush came at the public square before the cathedral, where stakes had been erected and dry brush piled beneath the little wooden platforms on which the condemned would stand.

Garcilaço found himself an advantageous spot atop a cask, from which he refused to be nudged by latecomers. Doggedly he held his ground, pushing off whoever threatened and once offering to climb down and fight a young man much bigger than he. When this fellow looked up and saw his opponent’s grim determination, hair in the eyes, scowl on the brown face, he desisted, left the cask, and elbowed his way to one less vehemently protected.

At noon, with the sun blazing overhead, Indian women sold in wooden cups cool potions of a refreshing drink they made from the sweet limes for which the valleys near the city were famous, and Garcilaço thirsted for his share, but since he had no coins, the women passed him by. However, a Spanish official who had purchased two cupfuls could not finish his second, and sensing the boy’s desire, handed him a generous leftover. As Garcilaço gulped the drink while the vendor impatiently tapped her foot, waiting for the return of her cup, the Spaniard asked: “You’re a mestizo?” and Garcilaço, between hurried gulps, said: “Yes, my father was Spanish.”

“How did he happen to marry …?”

“I never knew him. They tell me he was executed … before I was born.”

“Why?”

“Drink!” the vendor admonished him, and Garcilaço drained the cup.

“That was good. Thank you, sir.” The man was about to ask further questions when the boy’s master ran along the edge of the crowd in the open space where spectators were not allowed.

“There you are!” he shouted when he spotted his helper, and he was about to pull Garcilaço from his cask when the Spanish gentleman gave the older muleteer a hard shove: “Leave the boy alone.”

“The master hesitated a moment, but when he saw the quality of the man who had pushed him and realized that this stranger was probably from Spain and would have a sword ready for instant use if his honor was in any way infringed, he backed away, but from a safe distance he growled at his assistant: “Bad news! We must deliver our goods to the army in Guadalajara.” Since that city was more than a hundred and forty leagues to the west, Garcilaço knew that the journey would be a continuation of recent hardships, and that was bad enough, but now his master added: “You must come with me now.”

This Garcilaço did not want to do, for it would mean missing the auto, but his master was insistent, whereupon the Spaniard said in a low, threatening voice: “You, sir! Begone or I’ll have at you,” and off the master went, indicating by his furious stare that he would punish his refractory helper when the auto ended.

“How lucky you are!” the Spaniard said when the man had gone. “Guadalajara! Best city in Mexico.” And when Garcilaço asked why, the man said: “From there you can move on to the real west, and along the road catch glimpses of the Pacific Ocean. China! The Isles of Spice!”

He had served as a government official on the western frontier and said: “I’d always enjoy going back. You’re a lucky fellow.”

Now the real business of the auto began, with functionaries running here and there to ensure proper observances, and in the hush before the procession appeared, the Spaniard tapped Garcilaço on the shoulder and said: “Your master, he seems a poor sort.”

“He is.”

“Why don’t you run away? I did. From a miserable village in Spain where I was nothing. In Mexico, I’m a man of some importance.”

“I’d have nowhere to run,” Garcilaço said, whereupon the man grasped him by the shoulder: “You have the world to run to, my boy. You could be the new conquistador, the mestizo who will rule this country one day.”

“He corrected himself: “Who will help Spain rule it.”

“Look!” Garcilaço cried, and into the square where the kindling waited to be lit came four black slaves carrying the poles of a palanquin on which sat a prelate, dressed in deep purple and wearing an ornate miter, who stared steadfastly ahead. He was Bishop Zumárraga, most powerful churchman in Mexico and personally responsible for the arrest and sentencing of the two heretics who were to be burned. It was obvious from his stern countenance that he was not going to pardon the wretches.