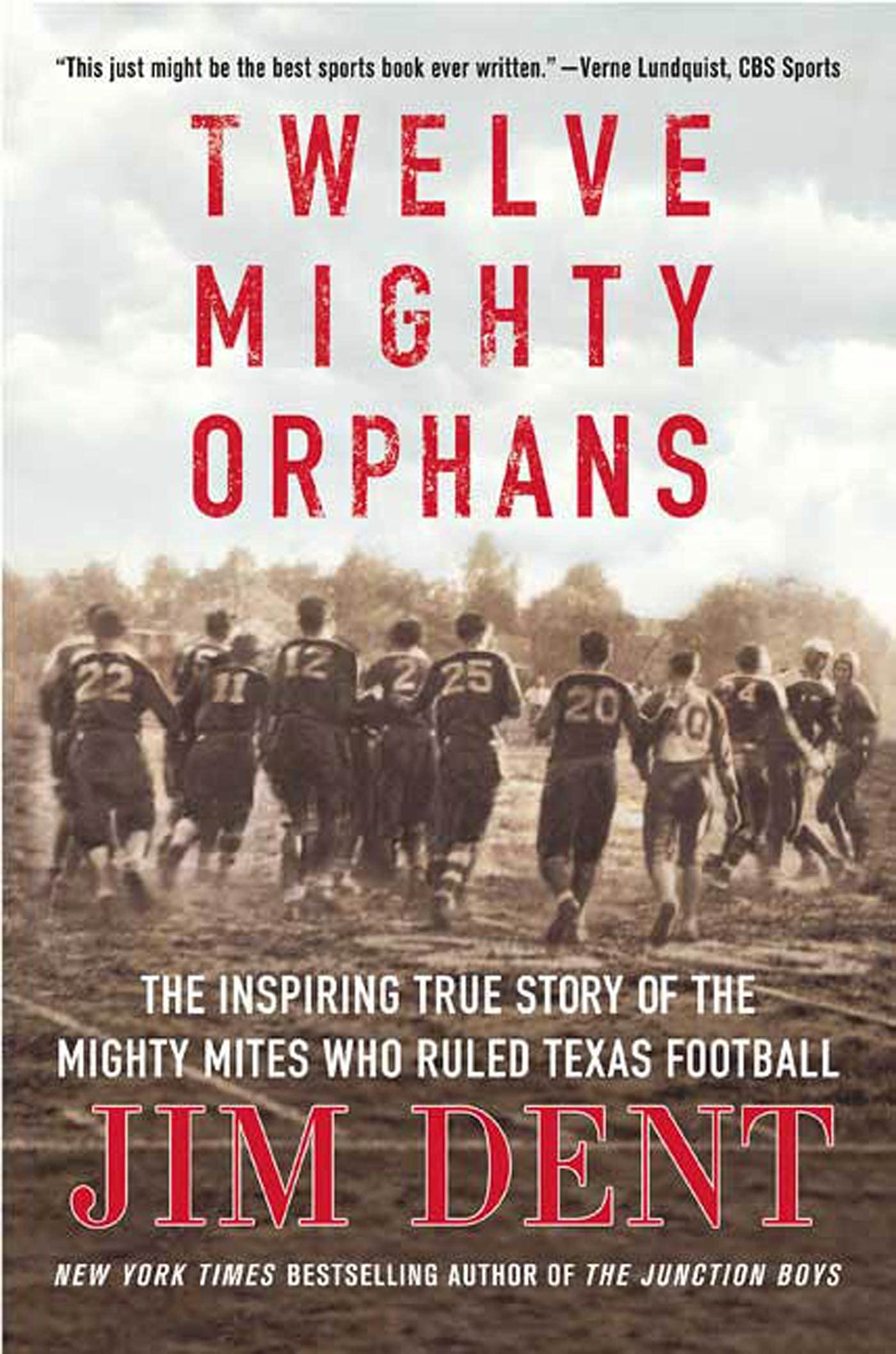

Twelve Mighty Orphans: The Inspiring True Story of the Mighty Mites Who Ruled Texas Football

Editorial Reviews

Review

“Dent builds a sense of drama and immediacy … This is Seabiscuit for football fans, sure to attract narrative nonfiction fans who like to mix sports, inspiration, and popular history.” ―Booklist

“The Mites’ story is inspiring.” ―Kirkus Reviews

“Incredible story…Dent’s strength is his play-by-play accounts of key games.” ―Publishers Weekly

“This just might be the best sports book ever written. Jim Dent has crafted a story that will go down as one of the most artistic, one of the most unforgettable, and one of the most inspirational ever. Twelve Mighty Orphans will challenge Hoosiers as the feel-good sports story of our lifetime. Naturally, being from Texas, I am biased. Hooray for the Mighty Mites.”

―Verne Lundquist, CBS Sports

“Coach Rusty Russell and the Mighty Mites will steal your heart as they overcome every obstacle imaginable to become a respected football team. Take an orphanage, the Depression, and mix it with Texas high school football, and Jim Dent has authored another winner, this one about the ultimate underdog.”

―Brent Musburger, ABC Sports/ESPN

“Read this book. You will think it’s fiction. You will think it’s a Hollywood script. But Twelve Mighty Orphans is the truth, and nothing but.”

― Randy Galloway, columnist, Fort-Worth Star Telegram

About the Author

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1From the front porch of the farmhouse near Kirkland, Maggie Ann Brown spotted the barefoot boy running from over a quarter mile away. His feet lifted small clouds of dust and his face showed the strain of his effort. Maggie Ann could not remember seeing her four-year-old run that fast.

Little Hardy Brown’s arms and legs were like miniature pistons. As he moved closer, Maggie Ann could see that he was mouthing words she could not hear. There was no telling how far he had come, or what he had seen, for the boy was a rambler and might wander the farmland all day, or fish the local creek until the rust-colored sun melted into the horizon.

Out in far West Texas, just south of the Panhandle, the land is covered in cotton and wheat and the grain elevators rise up like Greek temples. So flat are the plains that a silo some ten miles away seems to be sitting on your neighbor’s property. In the early summer, when the north wind gives up and the sun’s furnace kicks on, the ground starts to fracture and turkey buzzards take a rest. That July afternoon of 1928 was a scorcher, and Maggie Ann knew it was not advisable for any child to be working that hard.“Slow down, Hardy!” she yelled. “You’re going to bust a gut.”The boy darted through the front yard and his right foot kicked aside a tricycle. There was an assortment of children’s toys strewn across the bare ground, along with a tire iron and a rusted tractor engine.It was a typical shotgun farmhouse with a long, narrow hallway down the middle. “Shotgun” because, if you fired a shotgun from the front door, the shot would travel down the hall and straight out the backdoor. The place once belonged to a farmer, but a few years earlier he had gotten other ideas. The economy of Childress County was now booming, thanks to an abundance of cotton and wheat. Folks, in spite of Prohibition, were ready to party. So Hardy Brown Sr. decided to lay down his plow and crank up the whiskey still.

Stills, in fact.

So much potato whiskey was cooked up on the Brown’s ten acres that a twenty-four-hour guard was hired to keep the thirsty neighbors at bay. The sheriff of Childress County looked the other way as he pocketed his share, and the operation ran as smoothly as the old cotton gin out on the main highway.

Hardy Brown Sr. was a tall, dark-skinned man with thick sideburns that made his face look menacing. They said he had a lot of Comanche in his blood. The warring Comanches had ruled West Texas until the U.S. Army crushed them in the Red River War of 1874. Brown was thick with muscle and could lift a truck off the ground by laying on his back and leg-pressing it, and he did not mind letting people know that he would kick their dog asses if they decided to cross him.

This bootlegger was actually two people. There was also the happy family man who played with his kids and took them fishing. He had grown especially fond of Hardy Jr., the baby in the family, who feared nothing and was always into something.

Besides being the good father, Brown was also a fornicator and a fighter and a wild bull rider. Saturday nights in Childress, hundreds of people gathered to watch the men fistfight for fun on the town square. The local dairy owner would challenge the hardware salesman and they would duke it out until one fighter determined the other had the advantage. In the end, the two men would shake hands and go back to being friends and neighbors.

Few people wanted to tangle with Hardy Brown. Unlike the others, he did not view the event as “sport.” The man had killer blood in him. He could throw a pile-driving right hand that would send you to the hospital, or worse. The toughest hombres in the county had stopped accepting his challenges on Saturday night. So, he would simply wade into the crowd and start swinging.

It was little wonder that his rivals hated him. Whiskey money had transformed the laid-back cotton farmer into the biggest bootlegger between Fort Worth and Amarillo. He loved the fact that he ruled the world of outlaw whiskey. The once quiet county was now swarming with angry family clans. At the height of Prohibition, and just ahead of the Great Depression, the business of bootlegging had erupted like a West Texas gusher. The clans battled each other every day for money, turf, and moonshine. Highway 287 was a Texas version of Thunder Road. Whiskey stills around Kirkland were as prevalent as red dirt, the product as precious as a kiss from a Wichita Falls debutante.

Naturally, the hard-charging, stone-fisted Hardy Brown became the most despised man in the county. Driving Highway 287 between Childress and Kirkland one afternoon, he realized that a green Packard was trying to run him off the road. Never one to dodge a confrontation, he steered to the side as two men jumped out of their car. Brown did not reach for a gun or a knife or even a billy club from the backseat. He pulled out a singletree.

A singletree was like a long baseball bat with a hook on the end. The device was primarily used to hitch two plow mules together for the purpose of keeping them side-by-side. The first attacker did not see the blow coming. Brown swung the long club and watched the hook sink into the man’s skull. The second man tried to flee, but Brown pursued him, hacking away skin and clothing until he pleaded for mercy. He was left to suffer in a pool of blood.

As he drove away that day, Brown knew that a bounty would soon be on his head; men would come calling with killing on their minds.

A few days later, while walking along a country road with his four-year-old son, Hardy Sr. did not see the Gossett brothers step off the front porch and sneak up behind him with sawed-off shotguns. The twin blasts catapulted the unarmed man more than ten feet as a chunk of ribs and most of his spine were blown away. Little Hardy took off running and did not stop until he reached the family’s farmhouse some two miles away. Maggie Brown, now standing on the front porch, felt almost paralyzed when she saw the fear in her son’s eyes.

“Mama, they killed Daddy!”

“Where?”

“Up the road?”

“Who killed Daddy?”

“Them Gossett men.”

“How did they kill him?”

“Shot him in the back. Both of them.”

Maggie Ann was now in a panic. She dashed into her bedroom and inexplicably started pulling on stockings. She quickly put on a cotton dress and a pair of leather shoes and stashed some belongings in a cloth sack. Upon reaching the front door, she turned to her four children.

“Mama will be back just as soon as she can,” she said. “I promise.”

Maggie Ann took off running down the dirt road the opposite direction that Hardy had come. Every few steps one of her dress shoes flew off, and she finally tucked it under her arm and kept going. Her stockings split and now her exposed right foot was plastered with dust.

“Where is Mama going?” little Hardy said.

“She’s going to the train station,” his older sister Katherine said. “She’s getting out of this place.”

“Why?”

“She’s scared of them Gossett men.”In the days ahead, the four brown kids lived in constant fear of the Gossett brothers. Jeff, Rebe, Katherine, and Hardy slept together in the same bed every night with the covers pulled over their heads.

Mona, the oldest sibling in the family, who had married a few years earlier, tried to bring some comfort to the family. She returned to the house where she had grown up and was accompanied by her husband, Spurgeon Clark, who had been a business partner of Hardy Sr. Mona had some news.

“Fortunately, our daddy was a Master Mason in the local lodge and his dues were paid up. That qualifies all four of you to go to the Masonic Home down in Fort Worth. It’s an orphanage, you know. But I hear that it’s a pretty good place. Most of all, you will be safe there.”

Katherine began to cry. “I don’t want to go,” she said. “My friends are here. And we’ve got three cats and two dogs, and who’s going to take care of them.”

“I will,” Mona said. “You’ve got more important things to worry about, like getting an education. You will get some learning at the Home.”

Jeff cleared his throat. “When is Mama coming back?”

“From the way she ran out of here, never. I don’t think we’ll ever see her again in Childress County.”

“Doesn’t she love us anymore?” Katherine said.

“I haven’t talked to her and I don’t know where she is. But I’m sure she still loves you.”

Hardy Brown Sr.’s body was deposited into a pine box three days later and he was buried in an unmarked grave.

Not long after the funeral, a picture on the front page of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram showed hundreds of trucks and cars parked about the town square of Kirkland. The caption read, “Cotton Money Comes to Town.” A little farther down the page, a headline blared, farmer slain near childress.

The whole county was buzzing.

The Gossett brothers were arrested in a timely manner and then released on bond. George H. Gossett was the first to be tried in Childress County, and the result was a hung jury. Some said you could not find a single citizen in Childress County brave enough to convict a Gossett.

George H. Gossett’s next trial was moved to Donley in Clarendon County, and a change of venue sent his brother, Howard Gossett, to nearby Memphis, Texas. Both trials were to set to begin the next month.

When George H. Gossett’s trial ended in a hung jury, Spurgeon Clark decided to take matters into his own hands. More than just an in-law, he had also been a close friend and a loyal partner of Hardy Brown’s. The two had been inseparable at times, and some folks th…